If pop-up windows should mask page views then please close them.

Social History Notes

In the 19th century the majority of men in Hertfordshire worked on the land with their wives and families supplementing the family income with straw plaiting. Plait markets were features of country towns such as Hemel Hempstead and Hitchin.

Luton Museum and Art Gallery has exhibits of straw-plait making.

The straw of rye is tougher than that of other cereals and is valued for making straw plaits.

Hilltop Villages of the Chilterns – David and Joan Hay – Phillimore & Co Ltd

Straw Plaiters

By the early 19th century there are some signs of cottage industries, men and women who worked at home for factories or salesmen in the nearby towns. The parish registers record a razorgrinder, a chairmender, two shoemakers and a few lace-makers.12 These only employed a few individuals. The one cottage industry of real importance, an industry which occupied most of the women and children and some of the men as well in their spare time, was straw-plaiting. Introduced into England by Mary, Queen of Scots, who brought French plaiters over from Lorraine to teach the Scottish and provide employment for the women and children, it was transplanted to Luton by James I. Some of the credit for its spread amongst the villages may possibly go to William Cobbett who had advocated its introduction in his Cottage Economy and had given detailed instructions.13

‘From the information collected by my son in America.’

When he reached Tring in 1829 which, he wrote, ‘is a very pretty and respectable place’, Cobbett was delighted:

‘At the door of a shop I saw a large case, with the lid taken off, containing bundles of straw for plaiting. It was straw of spring wheat, tied up in small bundles, with ear on; just such as I myself have grown in England many times, and bleached for plaiting. I asked the shopkeeper where he got this straw; he said that it came from Tuscany; and that it was manufactured there at Tring, and other places, for, as I understood, some single individual master-manufacturer. I told the shopkeeper that I wondered that they should send to Tuscany for the straw, seeing that it might be grown, harvested, and equally well bleached at Tring; that it was now, at this time, grown bleached, and manufactured into bonnets in Kent...’

Whether he was successful in persuading the local farmers to grow the straw is uncertain, but it is a pity that his ride did not take him off the beaten track, up the muddy, stony roads to our villages where by this time he could certainly have seen the plaiters at work. Plaiting had indeed become so common an occupation that schools were set up where the children could learn the trade. There was one at St. Leonards, another at Cholesbury14 and a third at Wigginton. Children went to these schools at the age of four and were expected to make five yards of plait at the morning session, five more in the afternoon and another five at home in the evening with an extra yard at dinner and tea breaks, There can have been little enough time for learning letters, though at Wigginton the Dame, Mrs Osborne, had her own ways of educating the children.15 One of her pupils recalled that she used to read the Bible and poetry to the children as they plaited, and the daughter of this pupil who lives in Hawridge today recalls that her mother knew most of the Bible and ‘all the poems’ by heart. For attending these schools and working in overcrowded and unhygienic conditions, a fee of ld or 2d a week was charged, but as a child of 8 could earn 9d a week, it was still worthwhile. Indeed, later in the century when Church Schools were built, some of them allowed time for plaiting in order to get the children to attend.

We still have residents who know how to plait and for a description of the life we cannot do better than quote a first-hand account for, though these recollections date from the early 20th century, they would have been just as true if they had been written 100 years earlier.

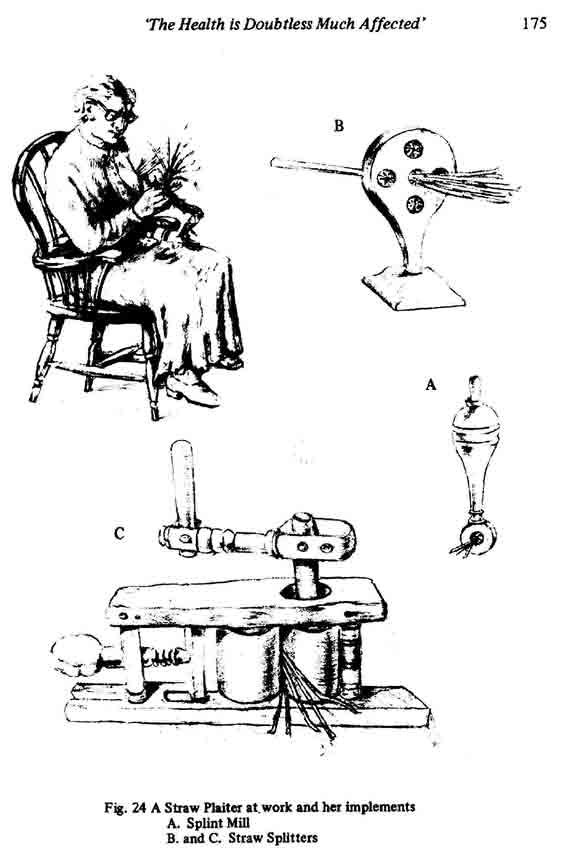

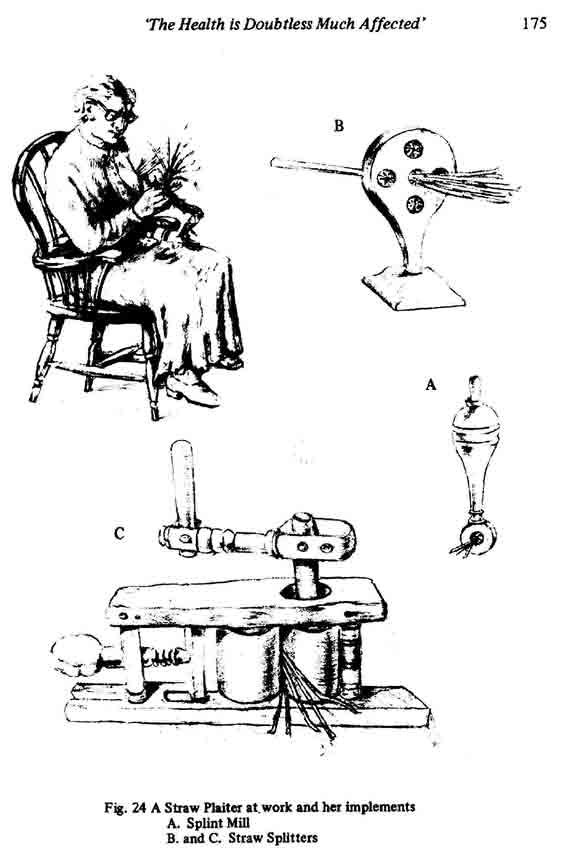

‘When my mother was a child she used to go to a plaiting school. She had to pay twopence a week and while she was plaiting she had to learn her letters. My very earliest memories of her are of her plaiting with one foot rocking the cradle where there was always a baby. She was glad to earn the very small pay for the plait as we were a large family and wages were very poor. When I was quite a small girl I used to go to the other end of the village to buy the bundles of straws from an old lady called Dinah. They were 2˝d. a bundle and I could carry 3 bundles in my pinafore. This was usually in my dinner hour from school and on the way back I had to collect from my granny the machine for splitting them. This my mother would do in the afternoon, then when I came out of school at tea-time I had to take back the machine and the straws my mother had split to be put through the straw miller; this was a small polished wood mill like a small wringer fixed on to the back of my granny’s door. She would slightly damp the straws, a handful at a time and put them through the mill. This was to make the straw pliable. When she had done them all I took them back to my mother and she was ready to start plaiting. She worked at it every spare minute she had. I cannot remember all the kinds she did, some 4 straw, 8, 12, 16, Satin, Feather-edge, Brilliant, also an open pattern made over a matchbox. It was sold by the score, 20 yard lengths, but first it had to be clipped, quite a long job, then wound from thumb to elbow and made quite smooth, then piled up in a clean cloth ready to take to the Friday market, piled up one end of the pram and walked into Tring where the dealers from Luton were waiting to buy. Sometimes these men would come up the hill to meet the women and offer to buy on the way, but prices varied and they liked to see what was being offered in the market. I wish I

could remember the prices but I had nothing to do with the selling as I was at school. My grandmother died in 1912 at the age of 76 so it is a long time ago. My mother used to tell us such stories about the plaiting school.

She said that some of the old dears used to have a device called a chad-pot. This was a pot with a lid with holes in it; they put in hot cinders and sat with it under their voluminous skirts to keep warm.’

The damping of the straws was done by mouth, and a commentator on this practice remembered that it was not only injurious to health because it was a sedentary occupation,

‘But when double plait is made, the health is doubtless much affected by the great loss of saliva, as each pair of straws is passed through the lips before being used.’16

The women would work at this for 12— 14 hours a day; even the children were expected to do their quota. A friend of Mrs Kingham’s mother, for example, had to do ten yards every night, when she was ten, before she was allowed out to play and in some cottages there were two notches marked on the mantelpiece to measure off the yards.

At the beginning of the 19th century, however, this was not an unprofitable occupation. Plaits with single straws sold at 1/- a straw for 20 yards—in other words a five-straw plait sold at 5/- for 20 yards and a good plaiter could earn 20/- a week. In 1827 it was recorded that not only was lace making earning a better price but, ‘The plait trade too has much improved; within the last month plait has been advanced to the retail trade from a shilling and fourteen pence a score to eighteen pence and in other sorts the advance is still more considerable.’17

By 1874 the price had fallen to 8/- when cheap plaits were imported from China.

Straw plaiting might be wearisome but it was profitable enough for the men to join in too, often working late into the night hoping that their earnings from this extra work would be concealed from the relieving officer.

Notes and References

1

2 Cholesbury Parish Register.13

Cobbett’s Rural Rides, Vol,II, p.273 (London, 1893).14

A Select Committee on Education of 1819 mentions the Cholesbury School.15

lnformation and following account from Mrs. Kingham of Hawridge, born and brought up in Wigginton.‘6 History of Wigginton, unpublished.

‘7 Gibbs, Vol.111, p.160.

‘A Little of my Life’, London Mercury, edited by J C Squire, Vol XIII, No 76, November 1925 – April 1926.

Lucy Luck - Straw-plait worker

Mrs Luck was born in 1848 and died in 1922 aged seventy-three; her husband died two years later, aged seventy-eight. Her memoirs were written towards the end of her life; her daughter says, ‘Mother used to sit and write it at night when she couldn’t sleep.’ She had a particularly unfortunate childhood in the workhouse, was orphaned early in life and had a succession of wretched jobs until she became skilled at straw—plait work; her married life in London, where she had seven children, was a happy, though still busy one. The account is emotional, in the style of a Victorian novelette, though there is no reason to doubt its accuracy.

I, L.M., was born on May 25th, 1848, at Tying, Herts. I was one of a family of four, the eldest a girl, nine years olS at the time I take you back to; she was a cripple with a diseased hip; the next, a boy between six and seven, and myself, a girl between three and four; the youngest, a baby in arms, a boy. My father I will sum up in a very few words. I had been given to understand he was an experienced brick-layer by trade, but was a drunkard and a brute. After bringing his wife and children to poverty and starvation he deserted them and left my mother to face the world alone as best she could with her family, and she never heard of him again.

What could my mother do but apply to the parish? — which she did, and the answer they gave her was, ‘You must go to the workhouse, and the Guardians will find, your husband.’ (But they never did.) There was nothing else for my mother but to go there.

Now the workhouse belonging to Tring was five miles away, and some sort of conveyance was provided for my crippled sister, but my mother had to get there as best she could with us others. She started to walk there, but as I was very young (not four years of age), I don’t remember much of that. I remember there was a man with a heavy cart going down the road, and he took us part of the way, until he turned up another road and then we walked on until we got to a school not far from the Union. There my mother sat down on the steps with one of us on each side of her, and one in her arms, crying bitterly over us before she took us into the Union.

I must tell you here, my mother had not been well since her youngest baby’s birth, through neglect and trouble. Well, I don’t remember much of what passed during my life in the Union. My sister was ill a long time, and was obliged to keep to her bed. Sometimes ladies would visit the Infirmary and give her dolls to dress as she sat in bed, but after a time (I don’t know how long) she passed away. I was allowed to follow her to the grave. I seem to see her now, being carried on the shoulders of the Union men.

Well! Time passed on, and my brother might have been nine years old (not any more). I know he was sent back to Tring, with another lad, to work in the silk-mills. Both were put to lodgings with the man who used to ring the mill bell.

There were two of us left in the Union then with my mother. I was sent to school; the same school where we had sat upon the steps previous to going to the Union, and going there seemed to press that one thing on my memory.

I cannot tell much more of what passed while I was there, except just one or two childish things. As I said before, ladies would visit the place, and once or twice give a threepenny piece to the children. Oh! how pleased we were. And weeks before Christmas we would cut pieces of paper in fancy shapes to put our Christmas pudding on when we got it. Another time, which I think was Good Friday, I was going out of the gates of the school, when a girl stood in the pathway with a basket of buns on her arm. She said to me, ‘Do you want any buns?’ and I said,’ ‘Yes, please.’ She then asked me for the money. I said, ‘I have not got any,’ and she answered. ‘Then you can’t have any buns.’

How disappointed I was! I quite thought she was going to give me one, and I cannot tell how many times I have thought of that Good Friday. And again, we used to have tin mugs for our gruel or milk, whichever we had, and wooden spoons. One morning my mug was half full of dry crumbs and the half-cold gruel did not wet it. I leave you to guess what it was like when I stirred ~t up. I have thought of it a great many times, particularly when I see paperhangers’ paste. You may think this a lot of foolish talk, but it is the truth…

…. Well, I was not quite nine years old, when I was sent back to Tring with another girl to work in the silk-mills. Now I had got my mother and brothers to see sometimes, but this other poor girl had not got a living relation, so you see she was worse off than I. We were sent to live with a Mr and Mrs D—, who had a son about thirteen and a daughter about fifteen years of age.

The first day I went to work I was so frightened at the noise of the work and so many wheels flying round, that I dared not pass the rooms where men only were working, but stood still and cried. But, however, I had to go, and was passed on to what was called the fourth room.

I was too little to reach my work, and so had to have what was called a wooden horse to stand on. At that time children under eleven years of age were only supposed to work half-day, and go to school the’ other half. But I did not get many half-days at school, as Mr D— was a tailor by trade, so I had to stop at home in the afternoon to help him with the work. But I have never been sorry for that, for I learned a lot by it. Neither was I eleven when I had to work all day at the mill.

I can fancy children now at that age, having to work from six o’clock in the morning until six at night. Every morning at half-past five the bell would ring out, ‘Come to the mill; come to the mill’. But still that would not have been so bad if we had a good home. But I was a drunkard’s child, and the ‘relieving officer’ had found us a drunkard’s home.

Mr and Mrs D— lived a most awful life, drinking, swearing and quarrelling. The son and daughter led us two girls a wretched life. We never had enough to eat, and I think everything that could be thought of by those two they did to worry and torment us. I don’t think Mr D— ever struck us, but I cannot say that of his wife. She was a most horrible woman, both in ways and looks, for she had a broken nose which disfigured her very much...

[After being turned out of the house] So you see what sort of a home the Parish found us; two poor girls cast out of home at three o’clock in the morning. God only knew where we were to lay our heads that night, for we did not. We wandered about until the old bell rang out, ‘Come to the mill’. Well, we went to the mill, and started work at six o’clock, and breakfast-time came; we had no home to go to now. There were a great many mill-hands who lived too far away to go home to breakfast, so boiling water was provided for each room. It soon got spread about how we two were placed, and one and another gave us to eat and drink, and we found we had more than enough. So you see there were kind hearts even there. Dinner-time came at two o’clock on the Saturday, the time we left off for the day, no home to go to.

We wandered on with the rest of the mill-hands, not knowing where we were going, but someone saw me, and told me I was to go and live wit~i Mrs H—, a poor but respectable widow with three sons and a daughter. It was a far better home than I had been turned out of. Mrs H— was a good woman. Now my money at the mill was only 2S. 6d. a week up to the time I left, and the Parish made this money up to 35. 6d., and that was all anyone had for keeping us parish children, as we were called. How could anyone properly feed hungry children upon that? So, to add to it a little more, I had to make five yards of straw plait every night after I had done work at the silk-mill. But I had a very good time there. I don’t ever remember one of them raising a hand to strike me. The Parish supplied my clothes; fairly good of the sort. I never remember having anything but cotton dresses, the old-fashioned lilac print capes like our dresses in the summer; and shawls in the winter; good strong petticoats and thick nailed boots, both summer and winter; big coal-scuttle bonnets, with a piece of ribbon straight across them. I leave you to guess what we looked like. I only remember having one plaything and that was a big doll that my sister had left me when she died. Soon after I had gone with Mrs H— to live, I was taken so ill in church one Sunday, I did not know how to get home. I could not eat anything all day, and on Monday morning I could hear the bell, ‘Come to the mill, come to the mill’. I did not know how to raise my head from the pillow to go to work that morning. I managed to get there somehow, and the master of my room was very good to me. He saw how ill I was, and knew how I was placed, and sent me to lie down at the top of the ‘alley’ as it was called. Now every day the overseer would go in each room, just before breakfast-time, dinner-time and evening. He would walk very slowly up the room, stop at every few steps, and then come back again, and then would be gone. The master would tell me to stand to my work until he had gone. This went on for a week, and I lost three quarters during that time, but that poor widow had to be the loser of that money. How I went to work that week God only knows...

Now, I had been with Mrs H— until I was thirteen years of age, and I— ‘Black Garner’, as he was called (the relieving officer), came to see her one day and said, ‘Fanny, I am going to take your girl away.’ She said, ‘Be ye, Mr J—, and where be ye going to take her to?’ He said, ‘I am going to take her to St Albans, to service. It is about time she was off our hands. Get her ready by next week.’ Yes! It was time I was off their hands, for I was costing then 9d. a week, besides clothing, and when I was obliged to go to him to ask for anything to wear, or to have my boots mended, he would treat me like a dog. A time or two, the boot-repairer could not mend them the same night, and he would lend me a pair. It did not matter about the fitting. Once he lent me a pair of button boots. I never had such a thing on my foot before...

The next week Mr J— came and said he would take me to St Albans himself. I had had a very good home with Mrs H— (and always visited them in after years). They bid me good-bye, and gave me a penny, then Mr j— and I started. When we got to Watford we had to change and wait some long time for the St Albans train; so he told me I could walk with him up the town a little way, and when we got to a restaurant he went in to lunch, but gave me a penny to Wait about outside...

Well, we reached St Albans at last, and the place of service he had found for me was a public house. What did it matter? I was only a drunkard’s child. But if they had found me a good place for a start, things might have been better for me. But there I was, cast upon the wide world when I was only thirteen years old, without a friend to say yea or nay to m~ Whichever way I took, I had only God above to guide me. The parish people sent me a parcel of clothes; no box to put them in. They had quite done with me now. The place where Mr J— took me to was very near the old Abbey. It was a double-fronted house, a shop and beer-house combined. Mr and Mrs H—, who kept it, were elderly people and had only been there one month themselves. They kept something of a general shop on one side of the doorway and a taproom the other. I know they had a cow, and a donkey, and I used to make butter and sausages, and sometimes serve in the taproom, and sometimes go out with milk. I know I was not much of a servant, for I had never been taught to do it. Mrs H— always had a charwoman in once a week, and this woman often told me her ‘wipes’ were better than my ‘scrubbing’, and I don’t doubt it. I always went to the Abbey on Sunday mornings.

My money was as. 6d. weekly, but my mistress spent it for me in getting me a few more clothes, and gave me a box to keep them in. She was very good to me, but after they had been there twelve months they were obliged to give the place up, and took a small cottage in a village between Watford and St Albans, and she could not afford to keep me; so I was obliged to make another shift...

[After two years in service in Kent and the death of her mother.] My mother died on Wednesday, August 5th 1863, and was buried on Saturday,.August 8th, with only the three of us to follow her. I was now turned fifteen years of age, just the time when a girl needs a mother’s care the most. Well, at my new place the mistress was very.good to me, but the master was one of the worst who walked God’s earth. Always fighting with his wife; the pots and glasses would go flying through the glass doors and windows, and he would beat that woman shamefully. On one Sunday night I bad my new mourning dress torn from my back, through trying to part them when fighting. But that was not the worst of him. That man, who had a wife and was a father to three little children, did all he could, time üfter time, to try and ruin me, a poor orphan only fifteen years old. He would boast to me, and even tell me the names of other girls he had carried on with. God alone kept me from falling a victim to that wretched man, for I could not have been my own keeper. It was impossible for me to stop where he was, and whilst I am writing here, I will tell you of Ms end. Some time after I had left, his poor wife died, and I was told he had shot himself.

By now I had begun to bitterly hate service, and a fatherly old man who used the public house where I had been, told of a place in Luton where they wanted a girl to learn the straw-work and help in housework. Although this was another public house, I thought it was a chance to learn a trade, so I went there. By the way, I stayed with this man’s wife until I was ready to go. He was what was called a packman in the country, one who travels to different parts of the country with a pack on his back; that was how he came to hear of the place at Luton. As I said before, I went there, and the place was very well and they were very good to me, but they did not keep to their promise. They would not pay me more than as. a week, but said they would teach me the straw-work. You may think it strange, straw business going on in a public house, but it was so, and I think the reason was, part of the business belonged to a sister and daughter. I sometimes did housework, sometimes served in the bar, and other times did the finishing of straw hats. They never attempted to teach me the making of them, but I was determined to learn, and would get a piece of straw and sit up half the night trying to do it. Now a girl with whom I had been out a few times told me of a woman who wanted two girl apprentices for six months, and would supply food, but no money. I went with her to see this woman, and it was agreed that we two girls should go there. I did not know if I was doing right or not, but as I had been some time at my place, and the money so little, and they had not shown me how to do the work, except the finishing-off (lining and wiring); I wanted to make the hats, so I made up my mind and left. I had a good lot of clothes, but not much money, and so I started right into the straw trade.

Hats were very different then to what they are now. I thought I was going to do wonders, but I think my real troubles had now begun. I liked the work very much, and was quick at it. I could do the two leading shapes of the season in a fortnight. but this woman set us a task every day which was impossible to do. I have sat up all night sometimes, in bitter cold weather, not daring to get right into bed for fear I should get warm and lay too long. I have even been obliged to do the work on Sunday, and then perhaps not finish the amount, and whatever quantity I was short she reckoned I was so much money in her debt. As I say, it was impossible to do in the time what she gave us, and so my little money went, and when that was gone she had my clothes just for my living. I don’t wish to boast, but I had kept myself respectable so far, and now this woman took in two other girls who had a most filthy disease, to sleep in the same bed as myself. Time went on like this for five months; at the end of this, the work began to get very bad. Mrs P— came back one morning in a shocking temper, because she could not sell the work, and brought home a new-shaped bonnet which she gave me to do. The first time I did it, it was wrong. I did it again; it was wrong. I did it a third time; it was still wrong. The day was more than half gone, and I had not done half or a quarter of my day’s work. I had only been taught just the two leading shapes, and it took much longer to do this new shape. But the season was over, and she had taken from me all I had got, and now she did not want me any longer. I threw the work down, and told her I would do no more, for I had got to that state of mind I did not care what became of me. That woman had taken all I possessed because I could not do the amount of work she set me, just for my food. I started out of that house that day, after having only been there for five months, with nothing but my mother’s Bible and a few little things tied up in a handkerchief. The season was over, and I was homeless, penniless, and with only the clothes I walked in. She had turned the other girl away, who went there with me, some time before, because she was rather slow at the work. What to do or which way to turn I did not know. Some people would say it was my own fault; I should have kept to service. Well, perhaps it was, but remember I was never put to a decent place at the beginning.

I wandered about; I did not care what became of myself that day. 1 had had no dinner, and I had nowhere to go, but towards night I thought I would try to find the other girl who had been there with me. I found her at last, with an aunt and uncle, and I told them how I was placed, and they, although strangers to me, took me in. This man said he had an order for work that would last for two or three weeks, and I could stop there and help to do it, and he would pay me what I earned. So you see, a home was again provided for me before night. I stayed there and worked as long as they had any to give me, and even after that, when there was nothing to do, I was allowed to stay, although they had not much room.

The work was very bad everywhere at this time, and I wandered about, trying for work, sometimes getting just enough to get some food; but I could not get any more clothes, and my boots were almost worn from my feet, often causing me to get wet-footed. How often I was tempted to lead a bad life, but there always seemed to be a hand to hold me back. I don’t want you to think I boast of myself, for I was not my own keeper, neither was I without faults; far from it. After a time, I got some work in a workroom, but I wanted a lot of improving before I could do it properly. So a woman in the same room undertook to see that I did my work correctly, and in time I was able to earn fairly good money now and then. I went to live with this woman, and on Saturday she would take my money and pay herself for looking to my work, and on the way home would meet two or three others, visiting different public houses. Often when I got home quite half of my money was gone...

Well, it happened again that there was not enough work at the room where I was, so I started out again to find more. I wandered about for some time, and at last I saw in the window of a very respectable house, ‘Good sewers wanted’. I went there, and the woman looked at me rather straight, and asked me several questions; where I lived, and where I had worked. I told her the truth, and she said she would give me work if I left that house at once, and would give me a home until I could find respectable lodgings. I went back to my place, and told them I did not owe them anything, for I had been earning very good money, but had not been able to do any good with it. They swore at me awfully, but the storm did not last long, as I had not many things to get together, and so I left bad company.

The first week I was at my new place, Mrs L— got me some new boots, and had one of her own dresses altered for me, got me other things, and I paid her something each week. I had plenty of work and a good home, but of course I was given to understand she could not keep me there, as there was not room. That woman was a true friend to me. I believe it was her who saved me from going quite to the wrong. When I had been there some two or three weeks (there was still plenty of work, and the card still in the window), a young woman called in answer to the card. She had come from a small farm just outside Luton, and Mrs L— gave her work. I asked this young woman if she knew where I could get lodgings, and she said, ‘I wish my mother would let you come to our house, for it would be company night and morning. I will ask her.’

Next morning she came with the answer that I could go there to live. I did so, and we went together to this same place to work as long as they could give it to us. I was now pretty comfortable, and began to get some good clothes; but after about three months, Mr and Mrs H— (the young woman s parents) left the small farm they were managing, and went to live in a village about three miles out of Luton. They wished me to go with them, so I did. We could not go into the workroom now to work, as it was too far away from Luton, but we had our work out to do, and used to take it in two or three times a week to Luton. Mrs H— as well as her daughter Sarah used to do the hat-work in the season, they were also both good straw-plaiters and would do that work in the dull season; but I was not much of a plaiter, and so would get what hat-work I could, or make children’s clothes for the village people...

While I was living with Mrs H— a young man who lived very near often came in to see Mr H—. He had driven a plough for him when a lad, but at this time he worked at a farm called Eaton Green, a farm between Luton and the village in which we lived. I leave you to guess whether this young man called mostly to see Mr H— or myself, but I had to put up with a lot of sneers from Sarah and her mother. It set me bitterly against him, and I told him I would not have anything to do with him; but one day when I was alone with Mr H— in the house, he put his hand on my shoulder and said to me, ‘My girl, you have poor Will; he will make you a good husband, and he will never hit you. Never you mind what Sarah or her mother says, you have Will.’...

After this, I began to think a little more kindly of W— L—. Soon after there was some unpleasantness between me and Mrs H— about my work, and she said some bitter things to me. I had sat night after night at work until eleven or twelve o’clock, using a rushlight candle, and my eyes had begun to get so bad that I could hardly see. It was about harvest-time and Will came as usual, and asked me plainly about getting married. Then I consented. He had been a steady, saving chap; if he had not got a few things together I could not have done so; so we settled it to be married about Christmas time. His master had a cottage to let at 25. a week, so he took it a few weeks before Christmas and got as much furniture as he could afford. I could not realize having a home of my own; I could not have thought more of it if it had been a palace.

I had been with Mrs H— now for nearly three years, and I left there on the Friday night as we were to be married next day. W— and myself went to Luton that night to do some shopping. It was a lovely night, although the snow laid thickly on the ground; the moon was shining beautifully. I went to my home (that was to be) for that night, as I had odd jobs enough to last me nearly all the night. My future husband and his brother, who was going to church with us, went off to bed, and a young woman, his cousin, sat with me until two o’clock, then went to her home and I sat in a chair and slept for a little while. That was how I spent my last night before marriage.

At five o’clock on the Saturday morning the weather changed; it began to rain fast and never ceased all day, and we had to start from home by eight o’clock to walk all the way to Luton. No carriage for us, as everyone looks for at the present time. I have often heard it said, ‘Happy is the bride that the sun shines on.’ Well, it did not shine on me that day, for the rain poured down, and the snow was sloshing under our feet; it was an awful day. To add to this misfortune, when we arrived at the church, we found all the doors closed. There had been some mistake, so we had to stand by while my brother-in-law-to-be went for the clerk. So don’t you think I had reasons to remember my wedding-day, which was on Saturday, December 21st, 1867?

After we were married, we went to a certain hotel where my brother-in-law was ostler, and went to his harness-room, where there was a good fire and something to eat and drink. After we had dried our clothes a little we started for home, a place I could now really call my own home. God alone knows how proud I was of it. My husband’s money was only 12S. a week, and at that time bread was 8d. a quartern-loaf; also meat, tea and sugar, and other things, were very dear. He had to be up every morning soon after three o’clock, as he had to walk two miles to work. I worked on as hard myself as ever I had done, so we got along very well, adding a little more to our home whenever we could.

My first baby, a girl, was born on January 7th, 1869. Things went on in a general way, living happily together but working very hard, and we found it difficult to keep things straight, and as time went on I had three little girls; the third one died at eight months and a fortnight old. That was a great blow to us. She was buried in the chapel grounds at a village called Brache Wood Green. It would, be strange to see a burial like that now, for we had six little girls to carry her to the grave. Soon after that we left that part of the country, and my husband went as ploughman to a farmer in the Dunstable road, near Luton. We had to live in a cottage belonging to the farm; there were four ivy-covered cottages standing by the side of the road for the workmen. It was there where my first boy was born; but he was very delicate, and when he was eleven months of age, there was an agitation among the farm—labourers for miles around, about the wages. Most of the farmers had agreed to give their men a little more; but not so with the farmer where we were. My husband’s money was only 13 shillings a week, and out of that 2 shillings went for rent, leaving ii shillings, with three little children to keep. So he asked for a rise, as other farmers were giving, but the master soon told him if he were not satisfied, he had better take a month’s notice and go. He did so, which meant getting out of the cottage as well. There was the worry then as to where we should go, or what we should do, but he had thoroughly made up his mind to go to London, and try to get work there...

Well, when our month’s notice was up, we could not get a house anywhere that we could afford, so we parted with a few things and packed the others up. I went to my brother-in-law’s with the three children till we could see what we were going to do, and Will, my husband, went to London to find work. He made his way for the Edgware Road, to a young man who had been groom at the same farm that we had left. He was at an hotel at work, and told Will of different places to go to for work. The first night he spent in London, he slept in a manger, and the rats ate part of his food which he had in his pocket while he slept. The next day he got lodgings near Paddington Green. It was on November 2nd when he went to London and on the 5th he got work as horse-keeper for a railway company, and I came to London a fortnight later, so that we were settled down in our home before Christmas, and so had our first Christmas dinner in London. I have reason to remember that dinner, for we had to have it by lamplight. It was a shocking day. I shall never forget my first two or three months in London. I think I cried most of the time, for my husband was on night work, and I amongst strangers and thinking of my poor child I had so recently buried. I would have given anything to have gone back to the country. I still kept on with my straw-work, as the person I worked for sent it up from Luton once a week, and I would send it back to the warehouse. Some months after, they forgot to send thread with my work on one occasion, which threw me in a great fix, as I could only obtain it in the City, and I did not even know for certain what shops or what part of the City. I was told by someone that they were sure I could get it at Whiteley’s, but I tried and could not, and went to Owen’s but could not gez it there, although I was told by them I could get it at the shop opposite, as they did the work for Owen’s. I went there, and saw the lady herself. She obliged me with the thread, and wanted to know a lot about Luton work, and told me if I would work for her she would pay me far better than I was being paid. So I finished up with Luton and worked at the shops in Westbourne Grove for thirteen years. I was in the workroom part of the time, and had my work at home the other part. My eldest daughter also worked for them for ten years. I should have stopped with them longer but the lease was up, and the shops passed into other hands that did not do that kind of work.

After that I went to another place in the West End, where I worked for one gentleman for twenty years. I always liked my work very much and although I had trouble with it when I first learnt, it has been a little fortune to me. I have been at the work for forty-seven years, and have never missed one season, although I have a large family. I have had seven together not earning a penny-piece. In my busy seasons I have worked almost night and day. I don’t like to talk of what I have done, but I generally bought up what I could at sales, and made up my children’s clothes in my dull season, and I don’t think I have paid away 30s. for any kind of needlework.

The straw-work is very bad, as a rule, from July up to about Christmas. During that time I have been out charring or washing, and I have looked after a gentleman’s house a few times, and I have taken in needlework. This was before any of my children were old enough to work. I have done my best to bring them up respectable.

I met a woman quite lately, whom I got to know soon after I first came to London. I had not seen her for many years, and of course she wanted to know how we were getting on. I told her, and she said, ‘I suppose you have got a black sheep amongst them?’ ‘I am pleased to say I have not,’ I said to her, and the woman seemed surprised. I have had my troubles with them, as any mother would have with a large family, but not one of them have brought us any sorrow or disgrace.

The Hemel Hempstead Gazette 19 Nov 2000

SO why was it that in the last century the women of Hemel Hempstead were renowned for their big lips and the women of Berkhamsted for their big (if you’ll pardon the expression) bottoms?

It was one of the fascinating stories about the straw plaiting industry that was passed on to us by Mike Stanyon, Dacorum Borough Council’s deputy heritage officer.

We asked Mike for help after spotting a late 19th century report in The gazette that Mr Walter Tipping from Cotterells had written to the Princess of Wales asking her to help beat off the import of cheap straw plait from China by buying locally made hats.

Mr Tipping’s point was that thousands of people in Herts, Beds and Bucks found employment and a living through the straw plait industry, but since the start of the imports from the ‘barbarous’ and ‘heathen’ nation of China the industry had become virtually non-existent.

Luton’s link with the straw plait industry through its hats is well known, but says Mike, Hemel Hempstead was Luton’s main supplier of plait and it was for this reason that the Nicky Line was first built to help take the plait to Luton. The line took some 15 years to get off the ground and it was during this time that the cheap Chinese imports did so much damage to the local plait industry. So by the time the trains ran, it was the London link that was really used.

Hemel Hempstead had its own plait market which was held behind the High Street off an alley that runs up the side of the Bell.

Trade was not allowed to start before the market bell was rung at 7am and you were in big trouble if you broke the rule. Some people got round it by setting off early and meeting the traders coming in from Luton just outside the borough to do business.

Business in Hemel Hempstead got so brisk that a bigger market was needed and the New Plait Market was opened to the rear and side of the Kings Arms.

Special types of straw for plaiting were grown locally and, said Mike, it was a real family cottage business. Father cut the straw and bleached it with sulphur. The women and children then made the plait.

Plaiting was also often done by children in plaiting schools. The idea was that the children should get some education as well as doing and learning plaiting, but in reality the children rarely learned very much. This practice was stamped out by the education act of 1870.

The plait itself could be used for other things apart from hats such as travelling cases and the backs of chairs.

Oh yes, that question of lips and bottoms. Well, Mike says that the saying was that Hemel Hempstead women had big lips because they sucked the straw to moisten it. But in Berkhamsted they weren’t into straw plait and sat making lace - it was all the sitting that gave them the big bottoms.

Mike adds that plaiting was a pastime you could carry out virtually anywhere, even standing in the street having a good gossip.

Home | Table of Contents | Surnames | Name List

This page was created 02 February 2007