If pop-up windows should mask page views then please close them.

Social History Notes

Hertfordshire Countryside – June 1999

Focus on William Cooper by Vivienne Smith

When young William Cooper arrived in Berkhamsted in the early 1840s, it is said he had just half-a-crown (l2.5p) in his pocket. He was, however, to leave a lasting impression on the town. For he founded an industry here which became celebrated around the world.

William Cooper was born on 26th December 1813 in Clunbury, Shropshire, on the Welsh border. The eldest child of William and Sarah Cooper, he came from a long line of farmers and farriers. In those days, farriers did not simply shoe horses. They were early practitioners of veterinary medicine, a trade in which William began to work at the age of 20.

A few years later, perhaps in an effort to improve his prospects, the young man moved nearer to London. Travelling to Berkhamsted by carrier’s cart, he took with him just one black carpet bag, complete with his pestle and mortar, the tools of his trade. A stranger to the area, he was at first treated with great suspicion by the local farmers, some even calling him a quack. But through hard work and perseverance, and his natural skill as a vet, he gradually won them over.

The bane of sheep farming at the time was a highly contagious disease called sheep scab. Caused by mites, it not only left the animal with extremely irritating sores. The sheep’s fleece and general health suffered, and in severe cases it even proved fatal. Over the years, all kinds of homemade lotions had been devised to treat it, including everything from tar to butter. Rather than just concoct another salve, Cooper decided to look for a method of preventing the affliction.

Conducting experiments in his own backyard, he tried out various ways of mixing arsenic and sulphur in solution. At last discovering the right blend of chemicals, the young vet invented the celebrated sheep dip which was to make his name. Keeping meticulous records of the process, he dried the product and ground it into a powder. This meant the dip could be easily dispatched in packages, and simply be mixed with water when needed.

Cooper began selling his dip in 1843, and for the first nine years he manufactured it all himself by hand. At the same time, he continued to develop his veterinary practice. Becoming an early member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, he studied there for two years and received his formal qualifications in 1849.

Three years later, following the remarkable success of his sheep dip, Cooper purchased land for new premises. In Ravens Lane, off Berkhamsted High Street, he built his first mill. Still intending to pursue his career as a vet, he arranged for stables to be included, so he could care for sick horses there. At first, Cooper’s Sheep Dip was the factory’s only output. But gradually other veterinary products were introduced, such as Cooper’s Fly Powder and Cooper’s Foot Rot Powder, as well as various seed dressings.

Before long, the work load was so great that Cooper was compelled to give up his veterinary practice. By now, he not only had the support of his wife Mary, who was fully committed to his schemes. He also employed several workers. Conscious of the noxious substances they were working with, he even supplied them with boots to protect their feet.

Although he was considered a benevolent employer, William Cooper also had a name for being short-tempered. Yet he was equally quick to forgive. His head foreman, George Dean, was sacked at least once a month, it seems, but Cooper always apologised and reinstated him the following day.

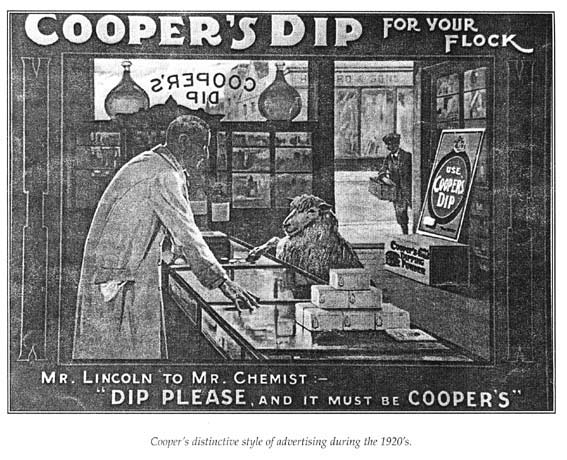

In 1857, the inventor of Cooper’s Sheep Dip began extending his factory. He also started up a printing house, naming it Clunbury House after his birthplace. Here, using a lithographic process, he produced labels and advertising posters which he had designed himself. It is said that Cooper was so pleased with his first colour poster that he marched through the premises with it fastened to his waistcoat.

Ten years later saw the introduction of steam power to the mills. A noisy innovation in its day, the first 6hp steam engine was nicknamed Vesuvius by the factory owner. But before long, steam power was being used in all areas of production, including the printing. Cooper’s business was fast becoming a leading employer in the town, and in 1868 more than 160,000 packets of sheep dip alone were sold.

It was around this time that the vet’s nephew, William Farmer Cooper, joined the company. Cooper himself had no children of his own, so one by one the sons of his younger brother Henry played their part in the family venture. The story goes that it was William Farmer who convinced his uncle to tackle the foreign market. The first overseas order was for the Falkland Islands, and by 1879 William Cooper and Nephews its first commercial traveller. Eventually exported to Australia, New Zealand, South America, South Africa and the USA, Cooper’s Sheep Dip was esteemed by the world’s foremost sheep farmers.

During the last five years of his life, William Cooper lived in semi-retirement in a large residence called The Poplars, not far from the site of his original mill. It was here that he died on 20th May 1885, at the age of 71, and all 120 of his workforce attended the funeral. In Berkhamsted Church, the Cooper family erected a memorial window to the enterprising vet, almost opposite the one that Cooper himself had dedicated some years before to his devoted wife.

Following its founder’s death, this famous company continued to prosper and in 1911 was appointed sheep dip supplier to the King. A respected manufacturer of agricultural and veterinary products throughout the 20th century, it became part of the Wellcome Foundation in the 1950s. Surviving several takeovers, Cooper’s of Berkhamsted finally closed its doors in 1997; more than 150 years after a young vet created his world-beating sheep dip here.

COOPERS

I was interested to read Vivienne Smith’s article on William Cooper and his sheep dip in the June edition.

The Trust was given a large amount of material relating to the company’s history when the factory in Berkhamsted closed in 1997. Readers may also be interested to know that when sheep dip production ceased in the early 1950s, the company (then known as Cooper, McDougall and Robertson Limited), was one of the first in the country to manufacture insect repellent in the form of aerosols.

We have recently loaned a number of the early aerosols to form part of an exhibition at the Robert Opie Museum of Advertising and Packaging in Gloucester, celebrating 50 years of the aerosol.

Matthew Wheeler, Dacorum Heritage Trust, Clarence Road, Berkhamsted.

Cooper’s Dip – For Your Flock

Neil Levitt

Over 150 years ago William Cooper arrived in Berkhamsted from Shropshire, a veterinary surgeon by training. In 1852 he established a small factory in Ravens Lane to develop and produce his invention, a patented sheep dip.

Little did he realise that very many years later his site would be condemned due to contamination from arsenic, not only the vast factory and office buildings but also surrounding homes and the ground on which they stood. Contamination had seeped deep into the brickwork and soil. Now these empty buildings are the responsibility of the present owners of the site, Glaxo Wellcome.

At its peak Cooper employed 1000 local people, and by the 1880s, production had reached 500,000 packets of Cooper’s Dip, and was exported throughout the world. His invention consisted of a mixture of arsenic and sulphur that was boiled to form a solution, heated to remove all moisture and then ground and milled into a powder for ease of transport. Production continued up to the end of the Second World War when new synthetic pesticides took over.

Following a merger with McDougall and Robertson, Cooper’s was one of the first to install an aerosol filling line and ‘Cooper’s Fly Killer’ and ‘Household Aerosol’ were well known brand names, and even in the 1980s, 600 were employed throughout the sites fronting the High Street and in the Ravens Lane complex. Due to a series of takeovers the Ravens Lane site became redundant in the 1980s.

It is to the credit of Glaxo Wellcome that they are now seeking the Dacorum Council to remove their restrictions on the land and buildings, and are applying for Conservation Area consent to take down the buildings. It is to be hoped that the authorities will not impose the same negative reply that has been the fate of the Rex Cinema on the corner of the High Street and Castle Street which has remained closed since 1973 and is now a listed building due to its foyer, staircase and art deco interior.

Owing to the contamination it will not be possible to convert the present buildings for further use, and the only solution is to take down all the buildings, and layers of soil dug up taken to special waste disposal sites. Only then when the site is clean could the owners consider a new development. It has been suggested that this would be an ideal site for starter workshops which are springing up throughout the country, and supported strongly by the present Government. Alternatively, the local residents would probably prefer to see the site become a mixed housing development which would ease the current need of 300 local families who are currently looking for homes in the area.

The former gas works on the South Bank of the Thames is a similar site that had to be ‘cleaned’ and is now the site of the Millennium Dome as well as substantial housing. As Britain’s largest industrial concern Glaxo Wellcome are now in the position to follow through the words of Kate Parminter, the Director of the Council for Protection of Rural England.

"This Council particularly supports schemes that rehabilitates derelict and contaminated land, returning it to the use of local people and helping to provide the affordable homes that Britain will need in the future."

William Cooper who lived for many years close to his factory in a very substantial house on the High Street, was reputed to be a workaholic but at the same time treated his workers fairly, in fact many of them stayed with the company throughout their working life. As an astute business man he would expect his assets to be used either for the furtherence of his business or invested in social and recreational facilities as he and his successors did in the town.

Now there is the opportunity for his current successor together with Dacorum Council to ‘dip’ the site for development.

Cooper’s

William Cooper was born in Clunbury, Shropshire in 1813 and by 1843 had arrived at Berkhamsted where he established a small veterinary practice. In 1849 he became one of the first practitioners to qualify from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. It is thought that at first he lived in a small cottage in Castle Street that was formerly The Sun public house, before moving to a small house in the High Street, from where he carried out a meticulous series of experiments. These mainly involved a combination of sulphur and arsenic and eventually led to the formulation of the world’s most effective sheep dip. In 1852 he established a small factory in Ravens Lane, built on land he purchased from Frederick Miller who owned the Pilkington Manor estate. here he could manufacture his yellow powder-based dip and inside the factory there were initially horse powered mills for grinding the ingredients and great kilns for boiling up the mixture. It was this innovative sheep dip which was destined to become the foundation for one of the world’s great veterinary and agricultural businesses. Steam powered machinery was introduced at Cooper’s in 1864 and, as demand grew, the business expanded rapidly. A convenient dwelling place was important to a workaholic like William Cooper. He soon built Clunbury House, close to the Ravens Lane works and, as profits accumulated, the construction of Sibdon House was financed in 1869. The factory in Ravens Lane was also extended three times during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Teams of carpenters were now employed to make the boxes to carry the dip and William Cooper was one of the first manufacturers in the Country to establish his own lithographic printing works. It was the job of the Printing Department to produce the bold and distinctive labels which were to make his products uniquely identifiable.

As business continued to grow, William was joined by his nephews, William Farmer circa 1865 and Herbert Cooper in 1879. The company then traded as William Cooper and Nephews and by the time of his death, at his home ‘The Poplars’ in 1885, William Cooper was employing 120 men. He was sadly missed in the town because, although a strict task master, he treated his workers fairly and many employees remained with the company throughout their working lives. A team of Cooper’s travelling salesmen ensured that Cooper’s sheep dip enjoyed huge export markets all around the world and in 1880 a new, larger factory was built. This was called Lower Works and fronted on to the eastern end of the High Street, on a site which had formerly been Key’s timber yard. To the rear of this new plant there was now a canal-side wharf, used for the unloading of the large quantities of coal, sulphur and arsenic required in the manufacturing process. In 1891 Richard Powell Cooper, who had joined the company on the death of William Farmer in 1882, became the sole owner of Cooper’s and in 1898 he was joined by his eldest son, Richard Ashmole Cooper, as a partner in the business. It was R. A. Cooper who was instrumental in setting up the first Cooper’s Research Laboratory in the office building at Ravens Lane. In 1905 Richard Powell Cooper was created a Baronet for services to industry. When R. A. Cooper eventually took over the business, following his father’s death in 1913, he was also serving as a Member of Parliament for Walsall. Under his leadership the company continued to expand and diversify; the original factory had become offices, with manufacturing activity now centred on the newer High Street premises. By this time the family had purchased a large mansion known as Britwell, near Berkhamsted Golf Club. Built in 1906. this house had served as the last home of Sir John Evans (1823-1908) prior to being acquired after the First World War by the Cooper family who re-named it Shenstone Court.

In October 1925 Cooper’s was merged with McDougall and Robertson to form the larger business of Cooper, McDougall and Robertson. From 1937 the company worked in association with I.C.I. to produce a range of horticultural products under the trade name of ‘Plant Protection’. Since 1929 Coopers had also been running a programme of top quality stock breeding at Home Farm in Little Gaddesden and in 1940 a new purpose built Technical Bureau was constructed adjacent to the main factory site in the High Street. In order to maintain its position as a leader in the industry, the family home of Shenstone Court was converted for use as Berkhamsted Hill Research Station and the laboratory facilities, first established at Home Farm in the early 1930’s, were moved here in 1952. The thriving printing department at Manor Street was now known as the Clunbury Press and began to undertake a variety of commercial work. During the immediate post-war period the first new synthetic insecticides began to appear and, as a result, the days of the powdered sheep dip were numbered. Production of the old powders ceased at Berkhamsted in 1952, but there was no danger of the company being left behind by its competitors, given the fact that it had invested so heavily in research and development. In fact the first aerosol filling line in the Country was designed and installed by McIntyre & Wallace in the Cooper’s factory at Berkhamsted. ‘Cooper’s Fly Killer’ and ‘Household Aerosol’ became successful brand names and the company soon diversified into other products like ‘Freshaire’ and ‘Hi Fi Furniture Polish’. By 1965 the 100th million aerosol had been filled at Berkhamsted. The company had been sufficiently profitable to invest in social and recreational facilities for its workforce. Cooper’s also had a thriving amateur dramatic group and back in 1922 a recreational club had been formed on land behind the newly built main factory. Here a large club house was provided in memory of R. P. Cooper and a bowling green was laid in 1932. Cooper’s also ran a sports ground with facilities for cricket and tennis on Kitcheners Field at the bottom of Castle Hill.

The advent of mass production meant that Cooper’s had to continue to expand to survive and in 1959 the business was acquired by the Wellcome Foundation. Following this take-over, the Cooper arm of Wellcome went on to enjoy further commercial success, with the development of anti-bacterial drugs for animals. However by 1962 much of the group’s aerosol production had been switched to Kelvindale in Scotland and by the early 1970’s only one in five of the Berkhamsted factory production lines was still in operation. By 1973 all former Cooper McDougall Robertson brands were being traded under the name of Wellcome. Cooper’s old printing department, then called the Clunbury Cottrell Press, closed in 1979 and the Research Station at Berkhamsted Hill was sold to an American health company in the 1980’s. In 1992 Wellcome sold its entire environmental health business, including the Berkhamsted site, to a French company, Roussel Uclaf. In 1995 the remaining group of Wellcome’s companies were themselves acquired by Glaxo, to form what was then Britain’s largest industrial concern. The Berkhamsted plant, which had been acquired in 1995 by the large chemical combine Agr-Evo UK, finally closed on 31st July 1997.

Richard Powell Cooper 1848 – 1913.

Sunday Times 15 Oct 2000

Just the place for a full and active retirement

Retirement developments have moved a long way from blocks of one-bedroom boxes with a bright red pull cord for an alarm and a warden to keep an eye on the residents. Nowadays, some developments are nice enough for people of any age to want to move in — although there is always an age limit of 55 or 60.

Castle Village in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, is one of these, converted from a mansion that was once home to Lady Cooper, whose family started the Wellcome pharmaceuticals company. The estate was used as the Glaxo Wellcome research centre until the early l990s.

It was bought last year by Ward Homes, which plans to have the retirement village (set in 20 acres) completed in a couple of years.

Home | Table of Contents | Surnames | Name List

This page was created 02 February 2007